It's 7:30 AM. Jessica reaches for her phone and begins scrolling. A video appears of a prominent scientist supposedly admitting that climate change data has been fabricated. It looks real, sounds real, and has 2.3 million views with thousands of shares. Her thumb hovers over the share button. She keeps scrolling and sees a “miracle supplement” that doctors supposedly don’t want people to know about, a fake-looking post about a celebrity’s death, and shocking claims about political corruption. After fifteen minutes, she’s seen a dozen posts. But how many of them are actually true?

She'll later discover the scientist video was a deepfake, the celebrity is alive, and the “miracle supplement” was a scam. This morning routine isn't unique. It's the daily reality of billions of us navigating an information landscape transformed beyond recognition.

The Misinformation Machine

Social media has become the modern public square, therefore a powerful tool for misinformation. What began as platforms connecting friends and family has transformed into the primary source of information for many in the 21st century. AI technologies and algorithms now drive what people see, believe, and share, creating an unprecedented mix of technological power and human psychology.

According to the Pew Research Center, 72% of U.S. adults now get news from platforms like Facebook, X, and TikTok (Pew Research Center, 2023). But here's the troubling part: false news spreads six times faster than truth (Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, 2018). Think about that for a moment. The lie races ahead while the truth struggles to catch up. Fake news tends to generate strong reactions, so people engage with it more and share it widely, which allows it to spread quickly.

Recently, researchers made a startling discovery about the COVID-19 pandemic and social media. The study found that 59% of the misinformation circulating during that period wasn’t outright lies. Real information was shared but was used out of context or manipulated (Brennen et al., 2020) to influence the public. For example, a genuine photo from 2015 becomes "evidence" of a 2020 event. A scientific study was stripped of its important warnings. Snippets from a politician's quote were edited to change its meaning. Pieces of truth were rearranged to create something false.

What is of concern is who is spreading the misinformation. The same study found that although only 20% of false claims come from politicians and public figures, they account for 69% of total misinformation engagement (Brennen et al., 2020). When high-profile voices spread falsehood and use their platforms to magnify their influence, social media algorithms amplify their reach even further.

What about the platforms themselves?

Research shows that many false posts go unchecked: 59% on Twitter, 27% on YouTube, and 24% on Facebook (Brennen et al., 2020). Most misinformation spreads freely online, reaching millions of people before it’s ever corrected.

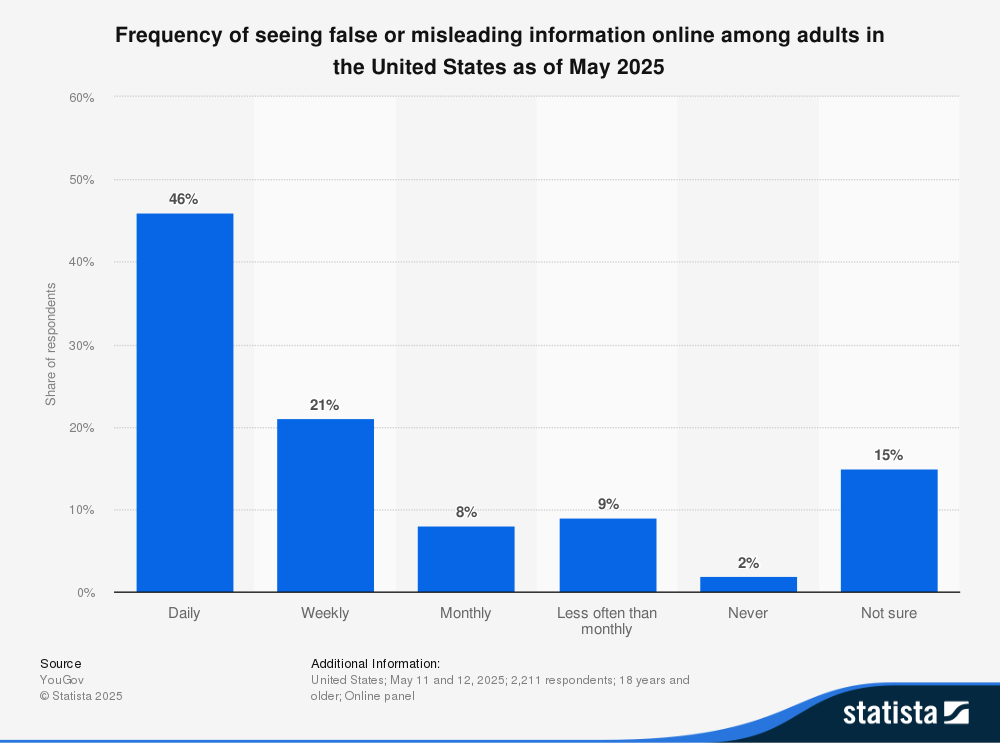

The graph below illustrates how often U.S. adults encounter false or misleading information online as of May 2025. Nearly half (49%) report seeing misinformation every day, while only 2% say they never come across it, showing just how common misinformation has become in daily digital life.

AI, Deepfakes, Cheap Fakes, and the Engagement Economy

Artificial intelligence has transformed misinformation from a human problem to an industrial-scale operation. AI tools like Sora and Midjourney can now generate convincing fake videos, images, and articles in seconds. The technology that once required expert-level skills now works with simple text prompts. Anyone can create a deepfake.

Perhaps more concerning are "cheap fakes," simple edits, or mislabeled content that don't require sophisticated AI tools. These spread even more effectively because they're easier to produce at scale and harder to detect through automated systems.

The fundamental problem we have is that platforms don't optimize for truth; they optimize for engagement. Algorithms have learned that outrage, fear, and community validation keep users scrolling longer than measured, factual reporting. Emotional content generates more ad revenue, creating a business model that rewards misinformation. The more outrageous the content, the more it spreads. The more it spreads, the more money platforms make.

How Human Psychology Fuels the Attention Economy

Human psychology makes us perfect targets as we are wired to respond to threats and emotional narratives. Social media algorithms exploit these natural tendencies, creating loops where we see increasingly extreme content confirming our existing beliefs while contradictory information gets filtered out (Tandoc & Maitra, 2018).

We don't just consume information anymore. We're being consumed by attention extraction systems that have learned exactly which psychological buttons to push. The algorithm knows what makes us angry, what makes us afraid, and what makes us share. And it serves us more of the same topic.

This "attention economy" has turned truth into a commodity. Platforms profit by selling access to our attention, creating incentives where the most engaging content, regardless of truthfulness, becomes the most valuable commodity. Content creators have learned that outrageous claims generate more views. Advertisers benefit from this heightened emotional state. Platforms profit from increased time on site. Sadly, truth is collateral damage in an economy optimized for engagement.

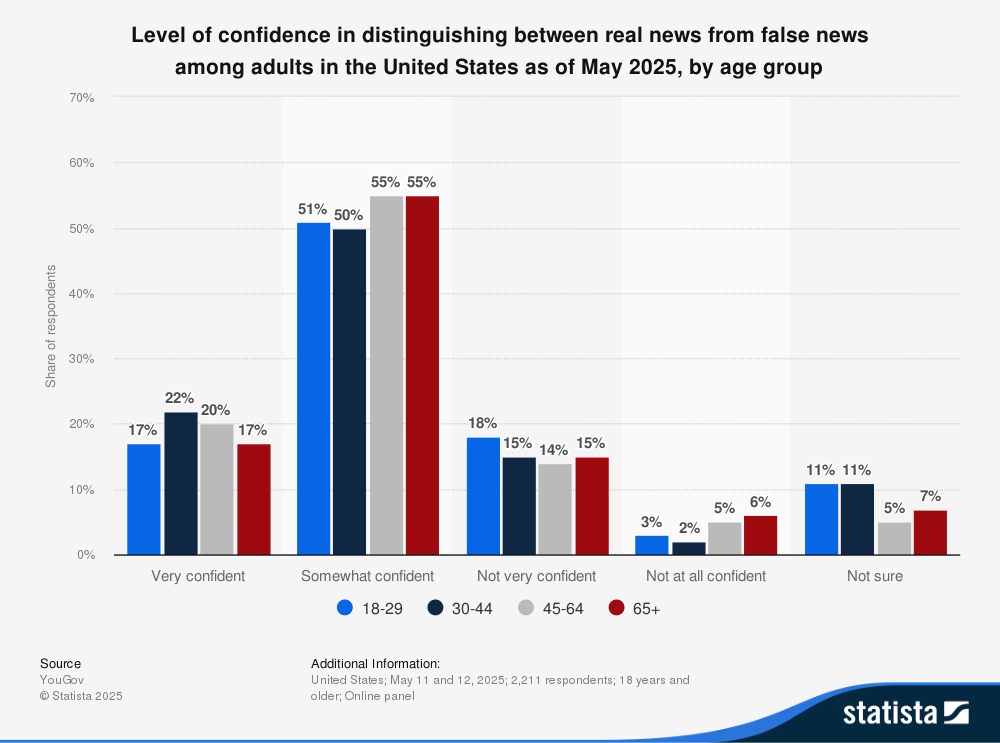

This graph illustrates how well people of different age groups can distinguish between real and fake news. While many individuals feel somewhat confident in their ability, a significant portion still struggles to tell the difference.

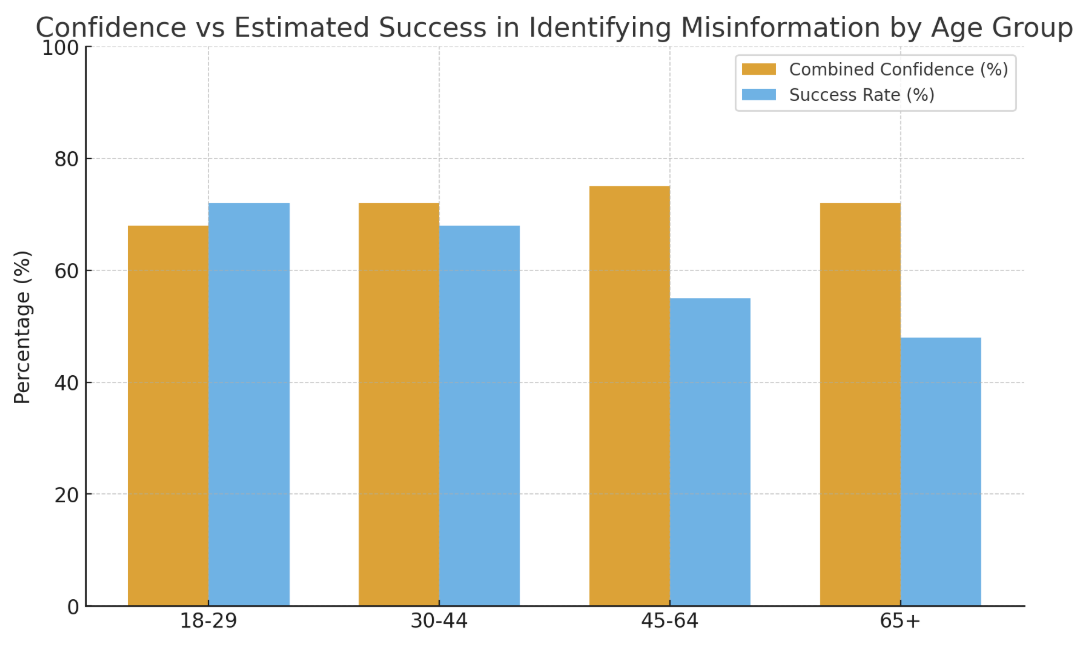

This comparison between confidence and actual success in identifying misinformation highlights a significant generational gap in media literacy. While older adults report the highest levels of confidence in their ability to distinguish real news from false information, their estimated accuracy is noticeably lower. In contrast, younger adults display more modest confidence but outperform older groups in correctly identifying misinformation, likely due to greater digital fluency and exposure to online media. This mismatch between perceived and actual ability underscores the importance of targeted media-literacy education, especially for older demographics, and demonstrates that confidence alone is not a reliable indicator of true digital discernment.

Impact on Society

The breakdown of a shared sense of reality creates serious problems for democracy. Trust in the media, government, and other institutions has dropped sharply over the past two decades, due in large part to social media and the spread of misinformation. When people can no longer agree on basic facts, meaningful political discussion becomes difficult. Politics devolves into tribal conflict, where the goal is to win rather than to seek truth.

Emotional manipulation is reshaping both political and consumer behavior in ways we're only beginning to understand. Campaigns increasingly rely on emotionally targeted appeals rather than policy arguments. Advertisers use sophisticated psychological profiling to exploit our biases. The result is a society where emotion overwhelms reason, and impulse displaces reflection.

What Needs to Change: An Ethical Approach

Addressing these challenges requires a multiple pronged effort. Education systems must prioritize digital ethics and AI literacy by teaching critical thinking skills adapted to the digital age. Students need to understand how algorithms work, how to evaluate sources, and how their attention and emotions are being manipulated. This cannot be a one-time lesson but rather ongoing education as technologies evolve.

Platforms should be required to disclose how their recommendation systems work, allowing independent researchers to check for bias and manipulation. The current "black box" system, in which algorithms are company secrets, is ineffective at maintaining healthy societies as social media companies have no interest in the upkeep and preservation of a working democracy. Transparency in how algorithms work is essential.

Inclusive AI design is necessary to prevent bias and exclusion. Development teams must include diverse perspectives, conduct rigorous testing for discriminatory outcomes, and build systems with fairness and transparency as primary design goals rather than afterthoughts.

Accountability and Oversight in the Age of AI

Global cooperation will be important for responsible AI and content integrity. Misinformation and AI-generated content do not respect national borders. International frameworks similar to those governing financial markets or environmental protection may be necessary to establish baseline standards while respecting cultural and political differences.

Regulatory action is already beginning. The European Union's Digital Services Act now mandates transparency from major platforms, requiring them to disclose how algorithms work and conduct risk assessments for systemic harms (European Commission, 2024). The United States is debating similar measures through the proposed AI Accountability Act (U.S. Congress, 2023).

The future may bring stronger penalties for misinformation and mandatory algorithm audits. Platforms could face significant fines for allowing widespread misinformation, creating financial incentives aligned with information integrity. Regular audits by independent experts could identify problematic algorithmic behaviors before they cause widespread harm.

Building a Digital Future Where Truth Matters

As we navigate this digital crossroads, our future depends on a shared commitment to transparency, ethics, and digital literacy—principles that can safeguard truth in an era shaped by AI-driven engagement. The fight against misinformation is urgent but entirely within our grasp, if we address it as a structural challenge rather than an individual failing. Regulation, platform accountability, and robust public education must work hand in hand, supported by communities of conscience that model responsible digital behavior. When small acts of verification become collective habits, they can strengthen democracy, protect public trust, and ensure that technology advances understanding instead of manipulation.

References

Brennen, J. S., Simon, F. M., Howard, P. N., & Nielsen, R. K. (2020). Types, sources, and claims of COVID-19 misinformation. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023, September 6). Employment projections and Occupational Outlook Handbook News Release - 2022 A01 results. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/ecopro_09062023.htm

European Commission. (2024). The Digital Services Act package. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

Pew Research Center. (2023). Social media and news fact sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/

Tandoc, E. C., Jr., & Maitra, J. (2018). News organizations' use of native videos on Facebook: Tweaking the journalistic field one algorithm change at a time. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1679-1696. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817702398

U.S. Congress. (2023). AI Accountability Act (H.R. 3369). 118th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3369

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

If you found this article informative & would like to support further research, click here to donate!