Nearly two decades later, the lessons of the Great Recession remain as relevant as ever

On October 9, 2007, the Dow Jones Industrial Average reached an all-time high of 14,164 points. Just 18 months later, it had plummeted to 6,547 points, a devastating 53% decline that epitomized one of modern history's most severe financial crises. Over 8.7 million Americans lost their jobs, millions more lost their homes, and the global economy contracted in the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

The 2008 financial crisis was not an act of nature or an unforeseen economic storm. As the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission concluded, it was "a human-made disaster shaped by systemic greed, widespread ethical failings, and regulatory complacency." The crisis emerged from a toxic combination of reckless lending, regulatory negligence, and a financial culture that prioritized short-term profits over long-term stability.

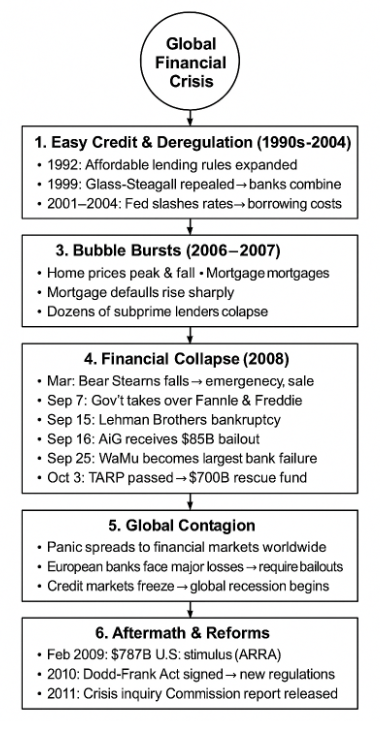

The Seeds of Disaster: Deregulation Opens Pandora's Box

The roots of the crisis stretch back to the late 1990s, when extensive deregulation fundamentally altered the American financial landscape. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, allowing commercial banks, investment banks, and insurance companies to merge. This removed barriers that had been put in place after the Great Depression to prevent conflicts of interest and limit risk-taking.

The deregulation continued with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which exempted derivatives, such as credit default swaps, from regulation. Proponents argued these changes would increase competition and allow American banks to compete globally. Instead, they created what economists would later describe as a "perfect storm" of systemic vulnerabilities, establishing an environment where complex financial instruments could proliferate without oversight.

The Lending Boom: When Accountability Disappeared

At the heart of the crisis was the widespread adoption of the "originate-to-distribute" business model. Banks could aggressively issue subprime mortgages to borrowers with poor credit, then immediately sell these risky loans to other institutions. This system eliminated accountability because the banks making the loans no longer bore the risk if borrowers defaulted.

The Federal Reserve's decision to slash interest rates to around 1% after the dot-com bubble burst further accelerated this trend. Between 2001 and 2006, subprime mortgages surged to nearly 20% of total mortgage originations. Banks loosened lending standards to unprecedented levels, offering NINJA loans (No Income, No Job, No Assets verification) and adjustable-rate mortgages with low teaser rates that borrowers couldn't afford once they reset.

Some economists sounded warnings. Robert Shiller repeatedly cautioned about the housing bubble, while Nouriel Roubini predicted in 2006 that a housing bust would trigger a broader recession. Brooksley Born, who headed the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, had warned about the dangers of unregulated derivatives in the late 1990s. But these voices were largely dismissed in an environment that embraced the belief that markets could regulate themselves.

Credit Rating Agencies: The Enablers

No institutions bear more responsibility than the credit rating agencies of Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch. These agencies faced a fundamental conflict of interest: they were paid by the same companies whose securities they rated. This "issuer-pay" model created perverse incentives that proved catastrophic.

The agencies routinely assigned AAA ratings to complex mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations that were far riskier than they were advertised to be. Over 90% of the AAA-rated securities issued in 2006 and 2007 were later dramatically downgraded. Internal emails revealed that agency employees were aware of declining lending standards but continued to provide favorable ratings to maintain their market share.

When these ratings were eventually corrected, the resulting panic sent shockwaves through global financial markets, revealing how the entire system had become dependent on fundamentally flawed risk assessments.

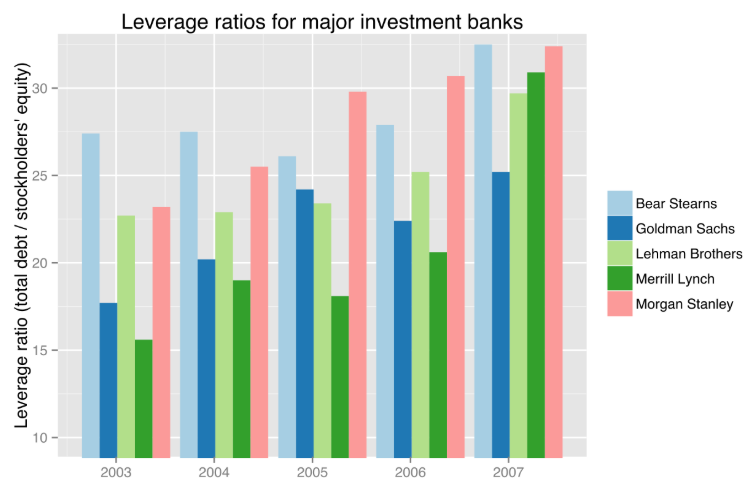

Excessive Leverage: A Recipe for Disaster

In 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission made a fateful decision, allowing major investment banks to dramatically increase their leverage ratios from 12:1 to as high as 33:1. This meant that a mere 3% drop in asset values could wipe out a firm's capital entirely.

Lehman Brothers exemplified this dangerous game. When it collapsed in September 2008, the firm held $639 billion in assets but only $22 billion in equity, resulting in a leverage ratio of nearly 30:1. The firm's failure triggered a panic throughout the financial system, freezing credit markets and creating a crisis of confidence that spread globally.

Meanwhile, the derivatives market had ballooned to $62 trillion by 2007, nearly four times the size of the entire U.S. economy. These complex instruments, originally designed to manage risk, instead concentrated and amplified it throughout the financial system. When the housing market collapsed, derivatives turned a correction into a catastrophe.

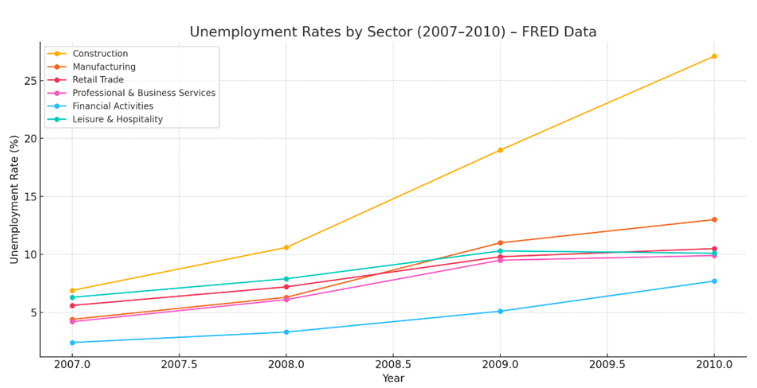

The Human Cost: When Wall Street's Failures Hit Main Street

The crisis's impact on ordinary Americans was devastating. Construction unemployment soared from 6.9% to over 27%. Home values nationwide fell by an average of 30%, with some regions experiencing declines of 50% or more. Retirement accounts lost 30.5% of their value, forcing millions to delay retirement or accept reduced benefits.

Despite this widespread suffering, remarkably few Wall Street executives faced criminal charges. The complexity of financial products and difficulty proving criminal intent allowed many to escape accountability, even as their institutions received taxpayer bailouts. This asymmetry of privatized gains during the boom and socialized losses during the bust became a defining source of public anger.

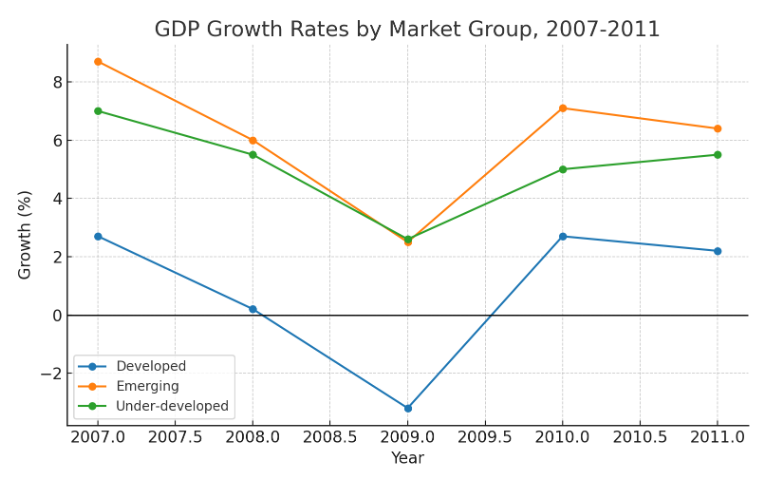

Global Contagion: How America's Crisis Became the World's

The crisis's international spread demonstrated how interconnected global finance had become. Iceland's banking system, which had grown to ten times the country's GDP, collapsed entirely when global credit markets froze. The crisis sparked the "Kitchenware Revolution" as citizens protested outside parliament, eventually forcing the government to resign. This was the first national leadership to fall directly due to the crisis.

Spain's housing bubble burst catastrophically, pushing unemployment above 20% and youth unemployment over 40%. Germany managed the crisis better through its "Kurzarbeit" program, which subsidized reduced working hours rather than allowing mass unemployment.

The BRIC nations of Brazil, Russia, India, and China faced a different challenge: collapsing demand for their exports. China's exports declined by 16% in early 2009, resulting in the loss of over 20 million migrant jobs. The Chinese government responded with a massive $586 billion stimulus package, while Russia suffered the worst decline as oil prices collapsed from $140 to under $40 per barrel.

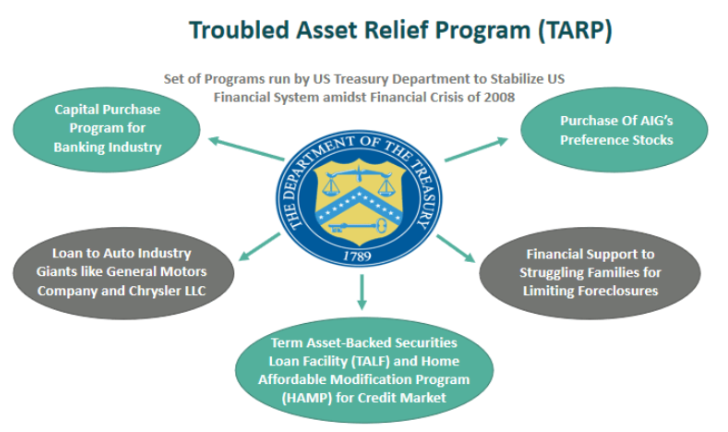

The Government Response: TARP and Its Aftermath

The U.S. government's response was unprecedented. The Troubled Asset Relief Program allocated $700 billion to prevent complete financial collapse, with about $444 billion ultimately disbursed. The program prevented economic meltdown and recovered about 93% of the funds, costing taxpayers a net $31 billion.

However, TARP sparked intense debate about "Too Big to Fail" policies. Critics argued that bailing out large institutions created moral hazard, the expectation that taxpayers would rescue them regardless of their behavior. Defenders countered that allowing major institutions to fail would have caused even greater damage, citing the chaos that followed Lehman's collapse.

Regulatory Reform: Dodd-Frank and the Fight for Accountability

The crisis led to the most comprehensive financial reform since the Great Depression. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to prevent predatory lending, implemented the Volcker Rule to limit speculative trading by banks, and mandated annual stress tests for large financial institutions.

However, these reforms have faced ongoing political challenges. The CFPB, designed as a key safeguard against the predatory lending practices that fueled the crisis, has been systematically weakened under the Trump administration. Acting directors have halted investigations, attempted mass layoffs of over 1,500 staff, and rolled back critical consumer protections, threatening to recreate some of the same vulnerabilities that led to the original crisis.

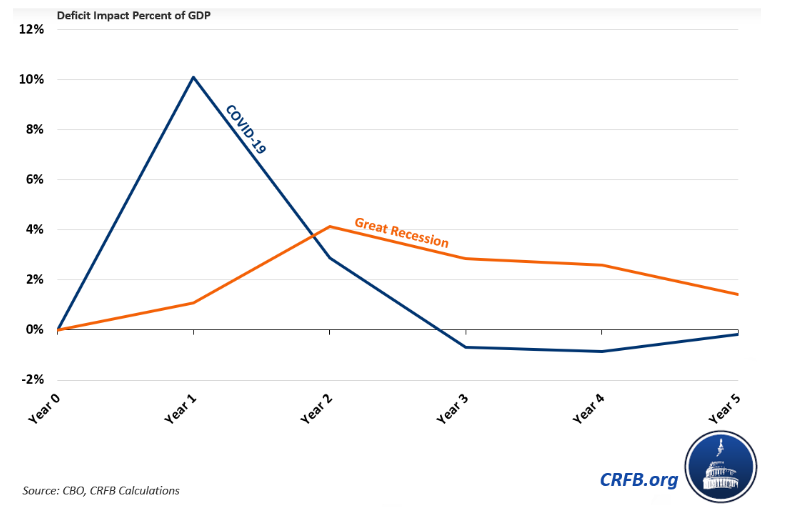

Comparing Crises: 2008 vs. COVID-19

The aftermath of both crises reveals striking differences in how societies respond to man-made versus natural disasters. Both required unprecedented government intervention and exposed deep vulnerabilities in economic systems, yet their long-term consequences diverged significantly.

The 2008 crisis sparked a prolonged reckoning with institutional accountability. Public anger over bailouts fueled political movements, from the Tea Party to Occupy Wall Street, while regulatory reforms, such as Dodd-Frank, attempted to prevent future misconduct. The crisis demanded fundamental questions about the social contract between finance and society.

The COVID-19 pandemic's aftermath, while economically devastating, generated diverse social responses. Rather than focusing on institutional punishment, societies emphasized collective resilience and adaptation. The pandemic accelerated technological transformation and remote work trends, but without the same moral imperative to restructure entire industries.

Both crises highlighted the tension between economic efficiency and stability, but with different lessons. The 2008 crisis showed how unchecked risk-taking by powerful institutions can devastate entire societies. COVID-19 demonstrated how external shocks can reveal the fragility of interconnected systems, but without the same questions of culpability and reform.

Lessons for Today: The Continuing Relevance

The comparison underscores that, unlike external shocks, the 2008 financial crisis was a preventable disaster that demonstrated how markets are not self-regulating, how complex financial instruments can create systemic risks, and how the costs of financial instability are borne primarily by those least able to bear them.

The crisis revealed several key vulnerabilities that persist to this day. Financial institutions remain concentrated and interconnected, creating ongoing "Too Big to Fail" risks. The complexity of modern financial markets continues to challenge regulators' ability to identify and address emerging risks. And the political influence of the financial industry ensures ongoing pressure to weaken protective regulations.

The Enduring Warning

The 2008 financial crisis was ultimately a crisis of ethics as much as it was an economic crisis. It revealed what happens when an entire industry loses sight of its fundamental purpose: to serve the real economy and the people within it. The human cost of millions of lost jobs, foreclosed homes, and depleted retirement accounts serves as a stark reminder that financial stability is not merely a technical concern but a fundamental requirement for a just society.

As we face new challenges in an evolving financial landscape, the lessons of 2008 remain as relevant as ever. The regulatory reforms implemented after the crisis represented important progress, but ongoing efforts to weaken these protections threaten to recreate the same vulnerabilities that led to the disaster.

The choice before us is clear: we can heed the lessons of 2008 and maintain the safeguards that protect against reckless risk-taking, or we can repeat the mistakes of the past and risk another devastating crisis. The millions who suffered during the Great Recession deserve nothing less than our commitment to ensuring that such a preventable disaster never happens again.

Until the lessons of 2008 are fully internalized across the financial system, the risk of another crisis remains ever-present, waiting for the next moment when greed overcomes prudence and regulation fails to keep pace with innovation.