In a remote village in Yemen, Abdullatif gathers bitter leaves from the halas tree and boils them into a thin, sour paste, the only meal his family will eat that day¹. Families in Yemen are forced to survive on what the land reluctantly provides due to famine, so for many, this desperate act has become the norm. Despite taking place in 2025, this imagery has a medieval feel to it. This level of hunger is caused by more than just a lack of food; it is also a result of poverty, displacement, war, and the collapse of the systems that once supported life.

Famine was officially declared in Gaza in 2025, and a similar tragedy is currently taking place there. With over 500,000 people in IPC Phase 5, the highest category of food insecurity, entire communities are experiencing catastrophic hunger. There have been reports of malnourished children in overcrowded hospitals, medical personnel treating famine with virtually no supplies, and families making do with animal feed or contaminated water⁸. The devastation of farmland, water systems, and the harsh limitations on humanitarian access are all factors contributing to Gaza's hunger - a man-made calamity under occupation and brutally destructive war.

The Mechanics of Famine

Famines frequently begin as drought, crop failures, natural disasters, or resource shocks, but they intensify when social and political structures collapse. This leads to a breakdown in distribution, so even when food is available, families may be unable to purchase it, access it, or have it delivered². Relief efforts to this are frequently derailed by the destruction or delay of aid, whether due to governmental policies, war, or blockades³. The crisis is made worse by the loss of hospitals, transportation networks, infrastructure, agriculture, and water systems⁴. In such crises, these forces come together to leave families with little choice but to survive on bitter leaves or sparse vegetation, a case we are also witnessing in South Sudan.

The Human Cost of Famine

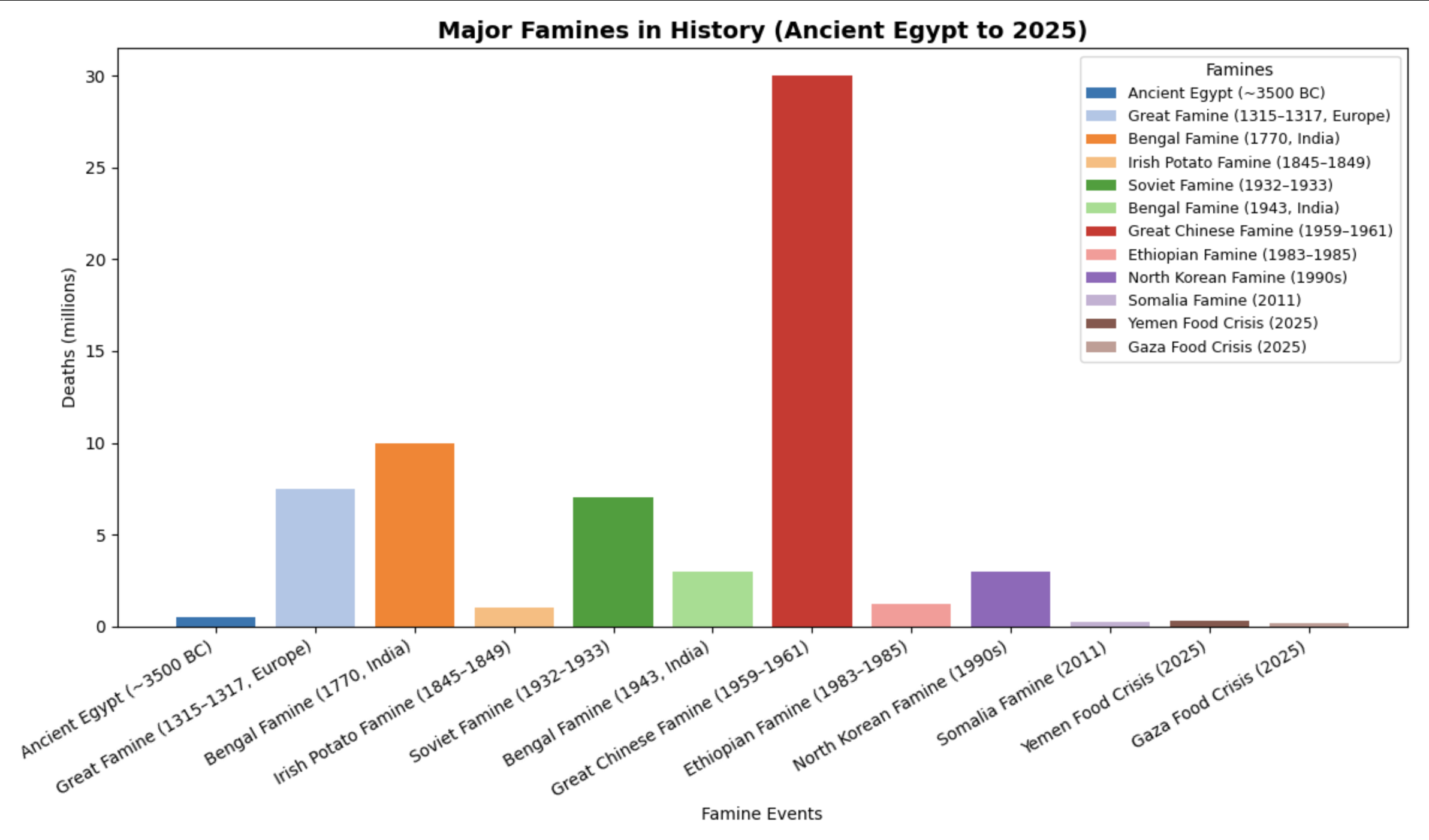

Famine is one of humanity’s oldest and most haunting crises. Not only are there empty plates, but entire lifestyles are crumbling as families are being uprooted, communities are being split apart, and social ties are being strained to their limit. Hunger had resurfaced with devastating force for centuries, from the ancient Egyptian floodplains to the potato fields of Ireland, the colonial Indian villages, and present-day disputes ranging from Ethiopia to Yemen. Every famine narrates a tale influenced by politics, war, and the unequal distribution of resources, in addition to drought or crop failure⁵.

Statistics by themselves rarely effectively convey the human cost of famine; survivor testimonies provide the most vivid picture. In Bengal in 1943, families trudged for miles in search of a handful of rice, while mothers pawned jewelry and sold what little they owned to feed their children⁶. During Ireland’s potato famine in the 1840s, families scavenged nettles and seaweed, as starvation claimed lives and left communities scarred with mass graves⁷. Today, similar scenes unfold in Gaza, where emaciated children lie in overcrowded hospitals, health workers struggle to deliver care, and daily deaths punctuate the collapse of social and medical systems⁸. Across time and geography, famine reveals itself as a profoundly human experience, shaping not just bodies but entire communities.

When Politics and Profit Deepen Hunger

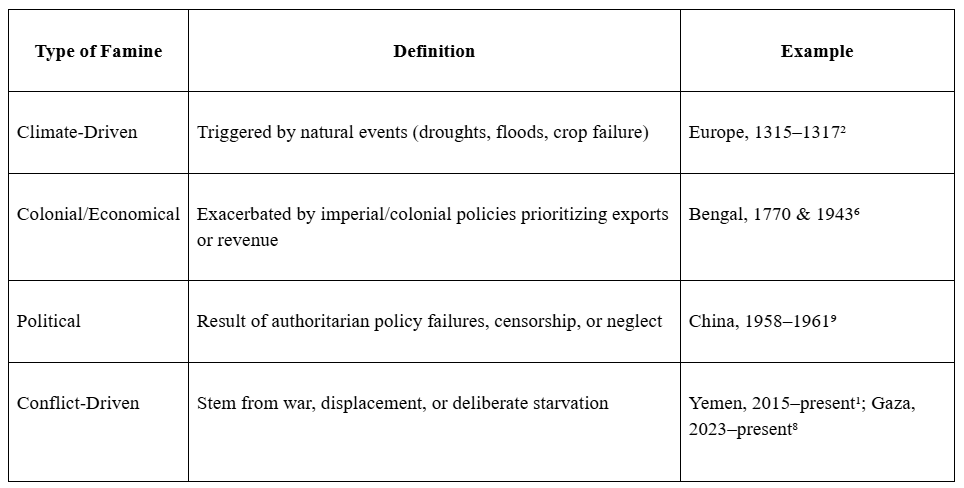

Famines are not only the result of natural or systemic failures; they are often exacerbated by economic or strategic interests that prioritize profit or power over human need. During the Irish Potato Famine, grain continued to be exported while people starved⁷. In Bengal in 1943, wartime priorities diverted food, while colonial revenue systems ignored the suffering of millions⁶. During the Great Chinese Famine, policy quotas and suppression of data worsened outcomes⁹. In contemporary crises, Yemen and Gaza demonstrate the same pattern: blockades, war strategies, and restrictions on aid amplify hunger and suffering¹,⁸. Recognizing the role of human choices in famine is essential: it means these tragedies are preventable, but only if political, economic, and humanitarian priorities center on human life over profit or strategy.

According to Amartya Sen's entitlement theory, famine frequently stems from people's ability to access food rather than its general availability. Who eats and who starves is often determined by trade systems, governance, and policy decisions. Preventing future crises requires an understanding of famine as both a natural and man-made phenomenon.

Timeline of Famines – From Ancient Egypt to 2025

~3500 BC – Ancient Egypt

- Cause: Irregular Nile flooding led to a seven-year famine, severely disrupting agriculture and society.

1315–1317 – The Great Famine, Europe

- Cause: Heavy rains destroyed crops across northern Europe, causing widespread starvation.

1770 – Bengal Famine, India

- Cause: Severe drought, compounded by British colonial policies, led to mass hunger.

1845–1849 – Irish Potato Famine

- Cause: Potato blight devastated the main food source, worsened by continued exports of grain to Britain.

1930s – Soviet Famines (Holodomor, Ukraine)

- Cause: Forced collectivization and state grain requisitions resulted in millions of deaths.

1943 – Bengal Famine

- Cause: Crop failures combined with British wartime priorities diverted food from vulnerable populations.

1958–1961 – Great Chinese Famine

- Cause: Policy failures during the Great Leap Forward, poor weather, and censorship of famine data contributed to widespread starvation.

1983–1985 – Ethiopia

- Cause: Drought, civil war, and political decisions exacerbated food shortages.

1994–1998 – North Korea

- Cause: Economic collapse and international isolation caused severe famine conditions.

2011–2012 – Somalia

- Cause: Civil war and prolonged drought led to acute food insecurity.

2015–Present – Yemen

- Cause: Ongoing war, blockades, and economic collapse. Many families survive on leaves from trees and sparse vegetation¹.

2023–Present – Gaza

- Cause: Prolonged conflict, occupation, indiscriminate use of weapons of mass destruction, destruction of cropland, restriction of water supply, destruction of hospitals and critical care infrastructure, and blockade of food and supplies to the vulnerable population

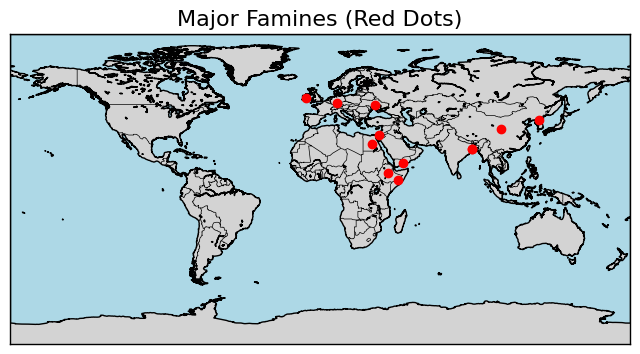

- Geographic Spread: The dots span multiple continents, highlighting that famines are not confined to one region or era; they've occurred in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

- Clustered Regions: South Asia (especially Bengal), East Asia (China and North Korea), and the Horn of Africa show repeated occurrences, suggesting systemic vulnerabilities tied to climate, governance, and conflict.

- Visual Simplicity: Without textual clutter, the map allows viewers to focus on patterns of location, making it ideal for pairing with a timeline or table for deeper analysis.

Types of Famines

Famines can be broadly categorized into overlapping types, reflecting both natural and human-made causes:

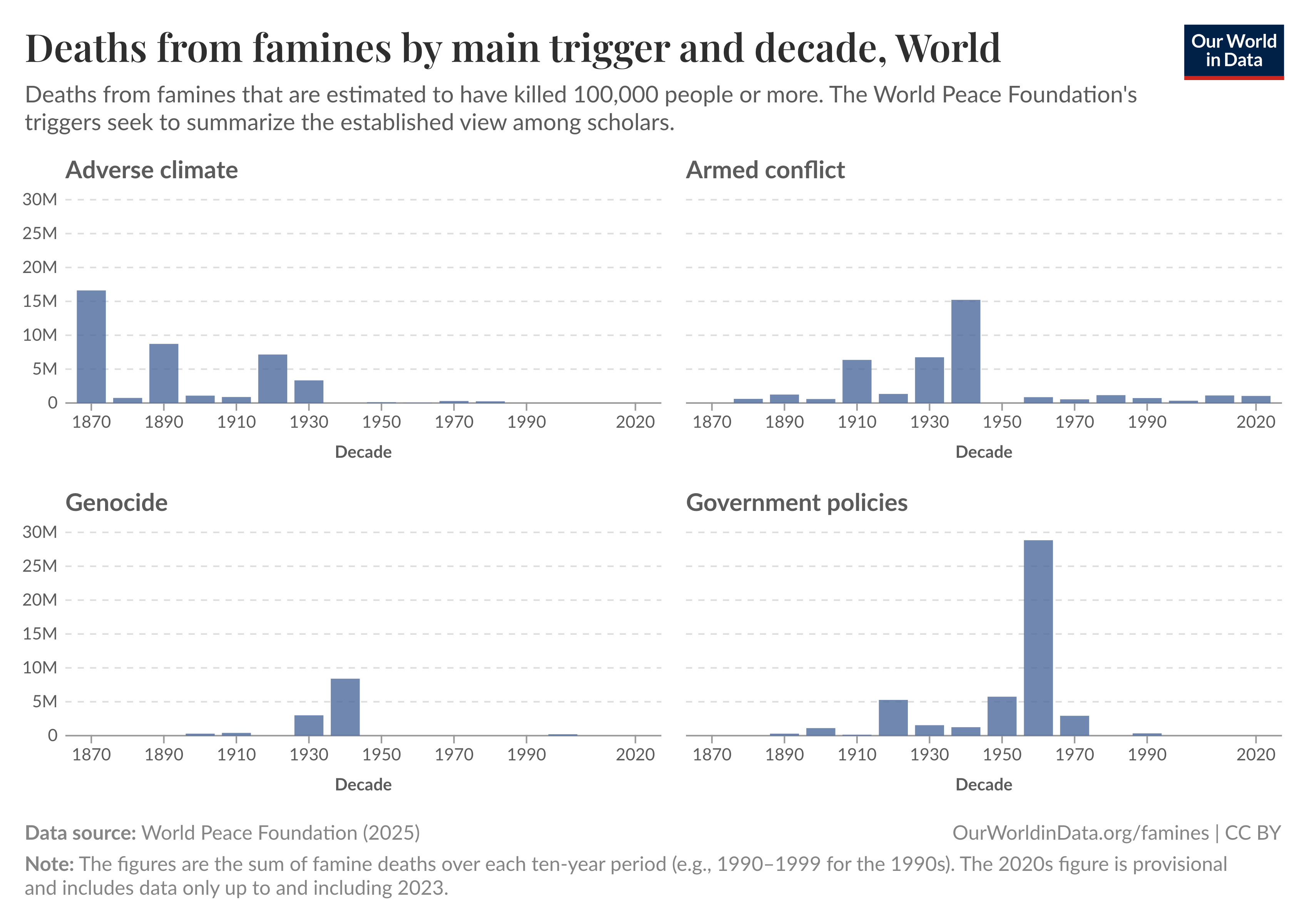

Understanding the Shifting Causes for Famine Deaths Over Time

This graph shows the number of deaths from major famines (defined as those that kill more than 100,000 people) by their primary cause and by decade, from the 1870s to the 2010s. Political choices, armed conflicts, unstable economies, and climate-related events are some of the triggers.

According to the data, the number of deaths from famine has drastically decreased over the previous century. Economic and climatic factors were the main causes in the early decades. However, a rise in politically motivated famines, frequently connected to authoritarian governments and ineffective policies, occurred in the middle of the 20th century. Despite a sharp decline in the total number of famine deaths, conflict has recently become the primary cause¹⁰.

References

¹ World Food Programme. (2023, October 10). Famine conditions in Yemen force families to eat tree leaves. https://www.wfp.org/stories/famine-conditions-yemen-force-families-eat-tree-leaves

²Sen, A. (1983). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation (Online ed., 1 Nov. 2003). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198284632.001.0001

³ Ó Gráda, C. (2009). Famine: A short history. Princeton University Press.

⁴ World Health Organization. (2025, August 22). Famine confirmed for first time in Gaza. https://www.who.int/news/item/22-08-2025-famine-confirmed-for-first-time-in-gaza

⁵ United Nations. (2025, March 6). Famine looms amid conflict, climate shocks. https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/03/1161471

⁶ Alamgir, M. (1980). Famine in South Asia: Political economy of mass starvation. Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain.

⁷ Kelly, M. (2020). The Irish famine: A documentary. Irish Academic Press.

⁸ FAO, UNICEF, & WFP. (2025, July 29). UN agencies warn key food and nutrition indicators exceed famine thresholds in Gaza. https://www.wfp.org/news/un-agencies-warn-key-food-and-nutrition-indicators-exceed-famine-thresholds-gaza

⁹ Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford University Press.

¹⁰Our World in Data. (n.d.). Deaths from famines by main trigger and decade. Retrieved October 1, 2025, from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-from-famines-by-main-trigger-and-decade