The story of interest begins long before banks, spreadsheets, or Wall Street — it began in the fields. Farmers from ancient Mesopotamia borrowed seed grain from temple granaries every spring, promising to repay more after the harvest. By about 3000 BC, this had evolved into a formalized system with the Code of Hammurabi that established maximum rates of 33⅓% for grain and 20% for silver. What we now call “interest” was then seen as a fair share of bounty, a reward for waiting, and a hedge against the uncertainty of seasons.

Interest emerged from necessity. Agricultural societies were bound to the rhythms of time. Seeds planted in spring would not yield until autumn, and life itself required faith in the future. The first lenders were temples, the earliest borrowers farmers, and the first financial contracts were carved onto clay tablets.

From these origins, interest reflected the earliest attempts by humans to quantify time. The loan of grain today meant repayment with tomorrow’s harvest. Time is transformed into a measurable and transferable cost. This transformation would become one of civilization’s most consequential inventions.

Yet from the beginning, the concept was controversial. The idea that time, a divine or natural force, could be owned or priced, provoked both awe and unease. The tension between interest as an enabler and interest as exploitation would define millennia of economic thought.

The Moral Backlash

The practice of lending had already spread across the Mediterranean by the time Greek philosophers began probing the nature of money. Aristotle, writing in the 4th century BC, condemned interest as an unnatural form of profit. In his Politics, he argued that “money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest.” To him, money was sterile — it could not reproduce. Earning money from money was a violation of nature’s order, an act of self-multiplying abstraction divorced from real production.

The critique was not merely philosophical. In Athens and later in Rome, debt enslaved people. When poor farmers defaulted, creditors could seize their land and labor. Debt bondage became a political crisis, driving reforms such as Solon’s Seisachtheia — literally “the shaking off of burdens” — in which Athens cancelled personal debts and freed those enslaved by them.

Rome’s legal system reflected a similar ambivalence. Interest was permitted but policed. The Lex Genucia (342 BC) banned it entirely for a time, while the Lex Unciaria later capped rates. The Roman Republic understood that unchecked interest could erode civic stability and compounding debt was not only an economic hazard but also a moral one.

Every ancient civilization wrestled with this dilemma. Interest was both vital and dangerous: it facilitated exchange but could enslave the poor. Mesopotamian kings occasionally declared debt jubilees, erasing obligations to reset the social order. It was an early acknowledgment that finance, if left unbalanced, could turn from a tool of cooperation into a system of control.

Faith and Finance

With the rise of the Abrahamic religions, moral scrutiny of interest intensified. The Hebrew Bible cautioned against charging interest to “your brother,” reinforcing social solidarity among the faithful. Christianity, extending that ethic universally, declared usury — any interest at all — a sin. Medieval theologians argued that time belonged to God, and to sell what was divine was to commit spiritual theft.

The prohibition was so complete that medieval lenders had to navigate elaborate theological loopholes. “Penalties for delay,” “partnerships in profit,” and “exchange fees” were constructed to mimic the economics of interest without invoking its name. But the moral logic persisted: profit without labor or risk was theft by another name.

Still, the practical need for credit never disappeared. Merchants financing long voyages or builders constructing cathedrals required capital up front. The tension between economic reality and moral idealism forced innovation. By the 14th century, Florentine banking families — the Medici foremost among them — developed instruments like bills of exchange that disguised interest within currency conversion rates. Commerce advanced under the thin veil of moral compliance.

Over time, the Church softened its stance. As trade globalized, the argument shifted from absolute prohibition to ethical moderation. Interest, once synonymous with sin, became tolerable so long as it was “moderate” and justified by risk. The moral battle ended not with theological victory, but with economic necessity.

In Islamic thought, the prohibition of riba reflects a parallel yet distinct moral stance, viewing any guaranteed gain without shared risk as a form of exploitation rather than legitimate exchange. While often simplified as "interest," riba historically referred more broadly to unjust, excessive, or unearned profit that allowed one party to benefit without reciprocal obligation. The Islamic tradition, therefore, developed interest-free financial systems designed around partnership, risk-sharing, and ethical trade rather than predetermined returns. This perspective adds another historical layer to humanity’s long struggle to reconcile finance with fairness.

The Rise of the Interest Economy

By the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, interest had been recast from moral hazard to economic foundation. The modern financial system — from national bonds to private credit — was built on it. Governments issued interest-bearing securities to fund wars and infrastructure; banks multiplied deposits through lending; and investors began to view interest as the price of time itself.

Adam Smith, while wary of greed, defended interest as a necessary mechanism for channeling capital into productive enterprise. By the 19th century, classical economists such as David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill had formalized interest within the theory of capital, as compensation for abstaining from present consumption and taking on risk.

This rationalization transformed moral suspicion into a mathematical principle. The time value of money became a universal axiom. Future cash flows could be discounted to present value; risk could be priced; and credit became the bloodstream of capitalism.

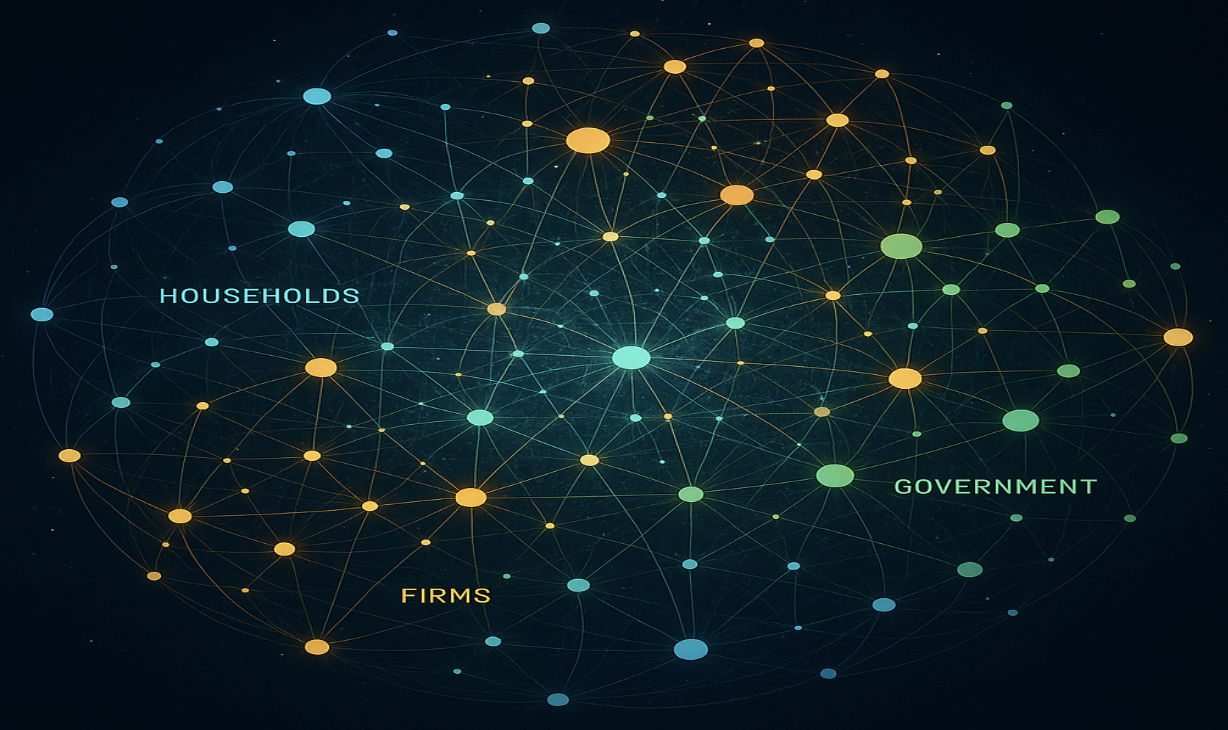

But the consequences were profound. For the first time in history, debt was institutionalized at scale. The relationship between borrower and lender was no longer personal or communal; it was systemic. Central banks began to set interest rates, and entire economies became adjustable through monetary policy. What had its origins in clay tablets had evolved into a global algorithm for controlling growth, inflation, and employment.

Interest and Inequality

Modern finance celebrates interest as a mechanism of opportunity, a way for individuals to buy homes, businesses to expand, and governments to invest. Yet the data tell a more complex story.

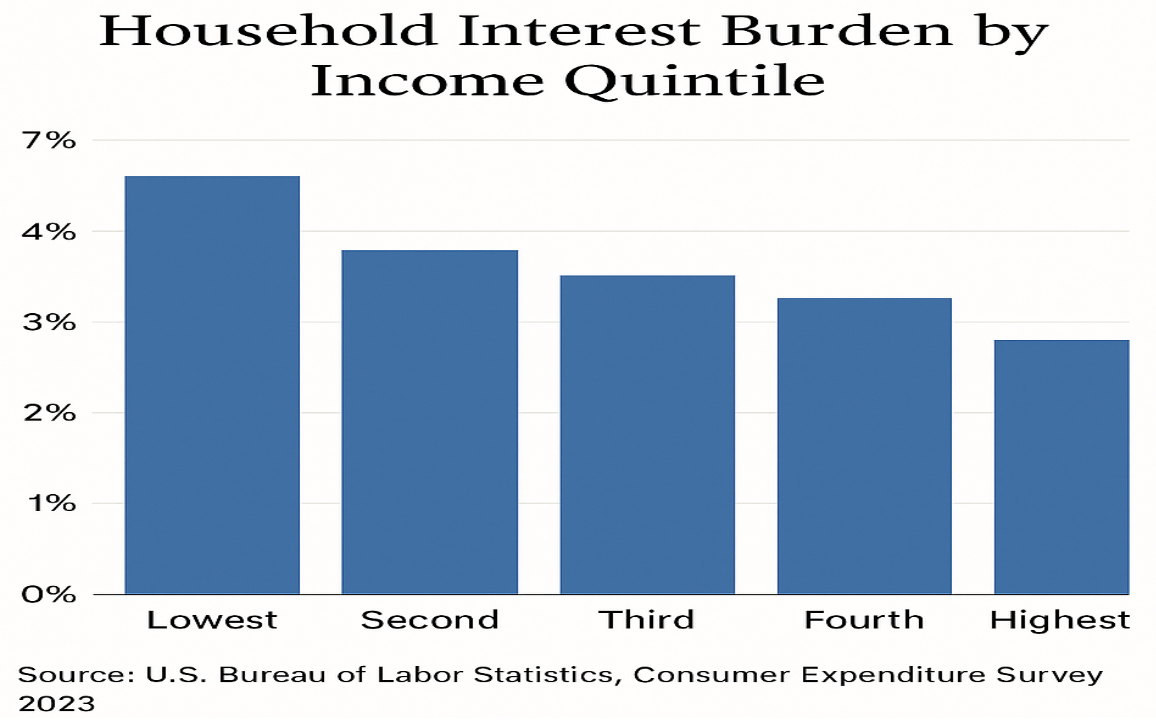

Households in the bottom income quintile devote roughly one-fifth of their disposable income to servicing interest-bearing debts — mortgages, car loans, credit cards, and student loans. For the top quintile, interest is not an expense but an asset, income from bonds, dividends, and capital gains. The same mechanism that promises mobility for some perpetuates dependency for others.

Consider the long-term compounding of a modest mortgage. A $200,000 home loan at 6% interest over 30 years results in more than $230,000 in interest payments, effectively doubling the price of the house. For the wealthy, lower interest rates, refinancing access, and tax deductions minimize that cost. For low-income borrowers, higher rates and fees make escape impossible.

Credit cards amplify this divide. With average interest rates exceeding 20%, the poorest households, those most reliant on credit for emergencies, pay the highest premiums. Default penalties and compounding charges turn short-term relief into a permanent burden. The lender profits most when the borrower struggles most.

In aggregate, interest has become a mechanism of wealth concentration. The top 10% of households now hold over 70% of financial assets in the United States, capturing the interest income generated by the debts of the rest. In effect, the poor pay interest; the rich collect it.

The Price of Debt

Interest’s influence extends far beyond households. Governments, too, are ensnared by compounding obligations. Public debt in advanced economies often exceeds total GDP, with annual interest payments consuming vast portions of fiscal budgets. In the United States, federal interest expenses surpass $700 billion annually, more than the entire education budget. Each generation inherits not only the benefits of past spending but also its accumulating cost.

Corporations operate within the same logic. Cheap borrowing in low-rate environments fuels stock buybacks, mergers, and acquisitions, often enriching shareholders while burdening firms with leverage. Rising interest rates reverse the cycle, forcing layoffs, slowing investment, and triggering recessions.

At the macro level, interest functions as the metronome of capitalism, dictating rhythm but rarely harmony. When rates are low, asset prices inflate and inequality widens; when rates rise, growth stalls and unemployment climbs. The mechanism that promises balance often delivers extremes.

Profit vs. Interest

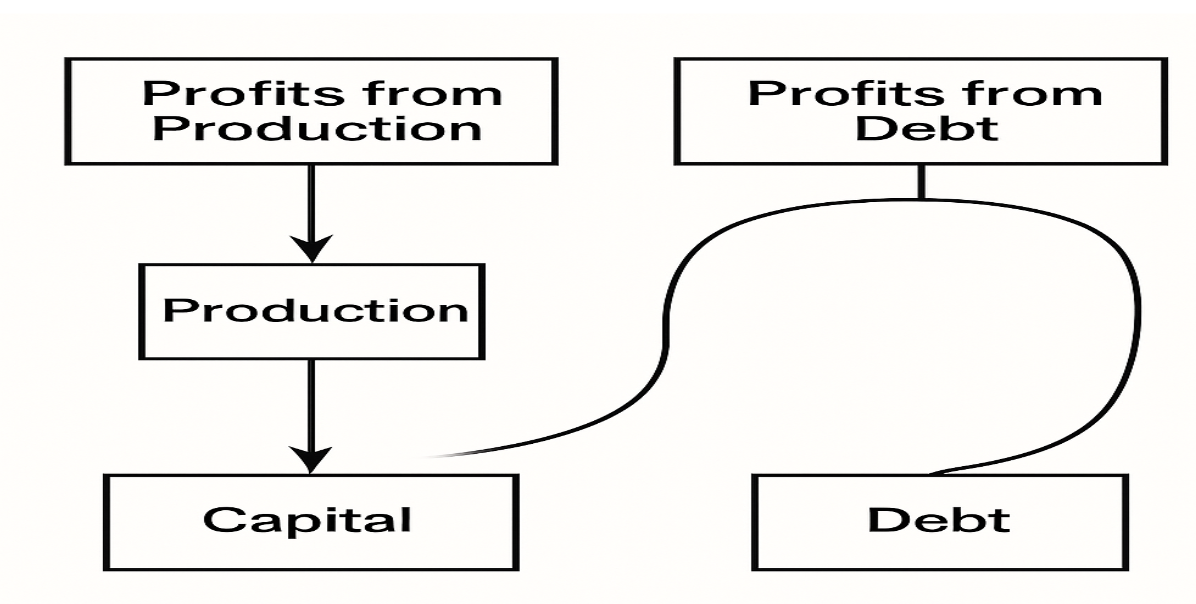

The defenders of interest argue that it is indispensable — the reward for patience, the cost of capital, the engine of efficient allocation. Critics counter that interest has detached from its productive purpose, fueling speculation rather than innovation.

Profit, in theory, arises from creating value. Interest, in practice, can arise from simply owning value — or the right to it. The difference seems small but is profound. A company that manufactures goods employs labor and bears risk; a creditor that collects interest merely waits. When waiting becomes more profitable than working, economies tilt toward rent-seeking rather than creation.

This is not an abstract concern. Over the past four decades, returns to capital have grown far faster than returns to labor. Corporate profits as a share of GDP have surged even as median wages stagnated. The S&P 500’s record valuations owe as much to financial engineering and low interest rates as to productivity gains. In effect, the system rewards the holders of time, not its spenders.

The Age of Dependence

Interest has become so embedded in modern economies that imagining a world without it feels impossible. Central banks adjust rates by fractions of a percentage point and move trillions of dollars. Housing markets, pension systems, and even currency values hinge on those decisions. Interest is not just a price; it is an organizing principle, a language through which the future is translated into present value.

Yet the dependence carries fragility. When rates rise, indebted households cut spending, firms cut jobs, and governments reduce services. When rates fall, asset bubbles inflate, and wealth concentrates. Economies oscillate between stimulus and strain, each adjustment trading one imbalance for another.

What began as a mechanism to bridge time has become a system that governs it. Interest dictates not only the pace of growth but the distribution of its rewards, who gains, who pays, and who waits.

The Timeless Dilemma

Across five millennia, the story of interest has been one of evolution and contradiction. Born in barley loans and temple ledgers, condemned by religions, philosophers and priests, resurrected by merchants, and perfected by financiers, it now underwrites the very fabric of modern economies.

Interest allows progress by mobilizing future resources but also perpetuates inequality by privileging ownership over effort. It is at once a tool of coordination and a weapon of control. The challenge for every era, from Hammurabi’s Babylon to the algorithmic trading floors of today, is the same: how to price time without devaluing humanity.

The modern economy must revisit the logic of interest itself, testing whether new mechanisms of shared risk and time-based value can replace a system that too often compounds inequality instead of opportunity.

If history teaches anything, it is that unchecked interest, whether moral, financial, or political, eventually demands repayment.

And time, as always, collects.

References

Interest Rates Old and New: How High is Too High?

The Long Tradition of Debt Cancellation in Mesopotamia and Egypt from 3000 to 1000 BC

Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989

If you found this article informative & would like to support further research, click here to donate!